People in the energy industry don’t have the Oscars. For us, the big event of the year is CERAWeek — a conference stuffed with CEOs, top policymakers, and environmental and energy wonks held annually in March.

CERAWeek 2022, with the theme“Pace of Change: Energy, Climate, and Innovation," meant the return of in-person activations, panels, and networking. Walking and talking between sessions and around the coffee table, it occurred to me that the unofficial theme of the event was “Maybe now we can find middle ground on energy.” This idea came up time and time again, from all kinds of people.

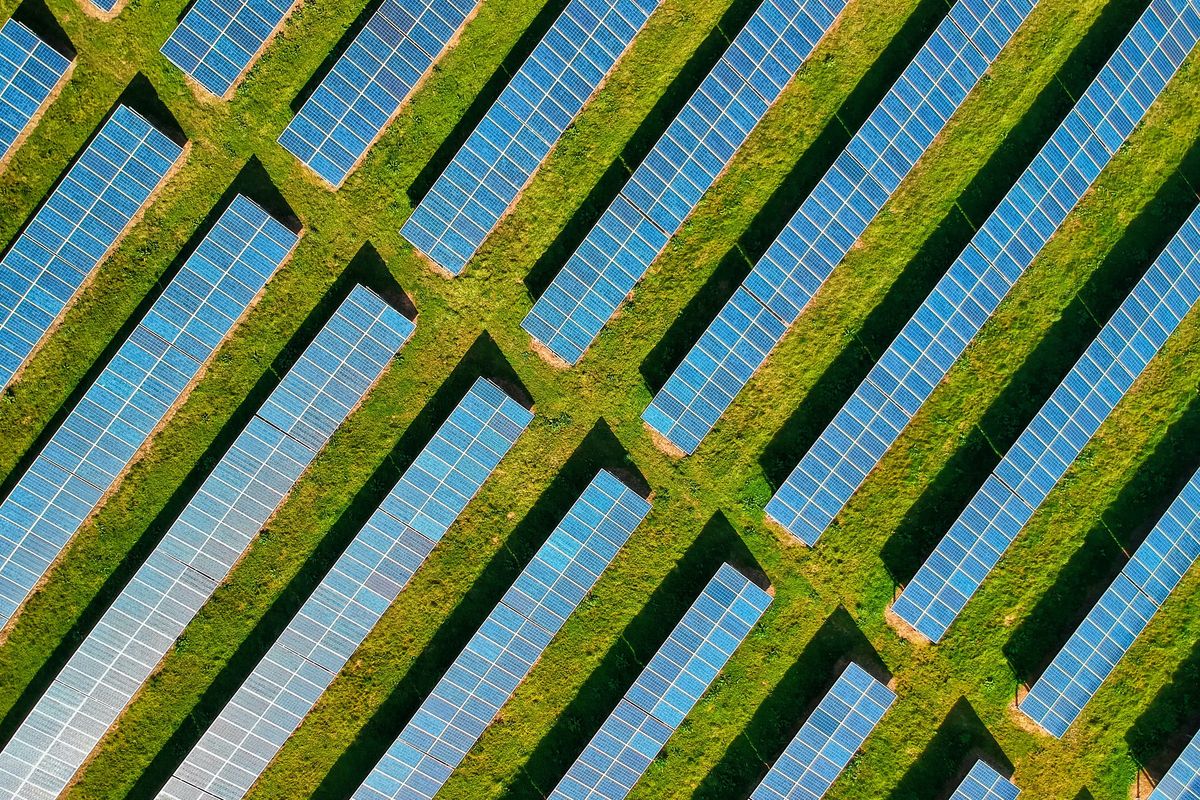

As with too many other issues, the discussion of the future of US energy has become polarized. On one end of the spectrum are those who want everything renewable and/or electrified by ….. last week, whatever the cost. Their mantra for fossil fuels: “Keep them in the ground.”

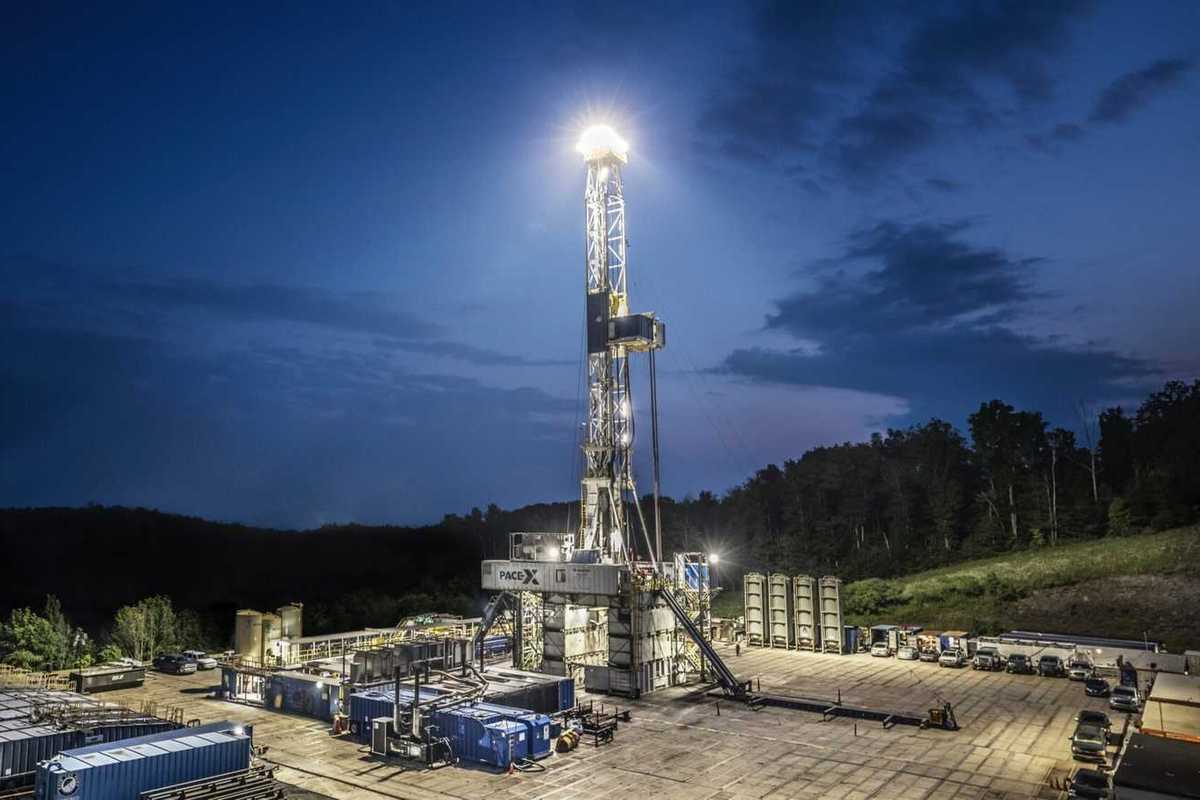

On the other end, are those who dismiss climate change, saying we can always adapt and that it doesn’t much matter, anyway. Just keep digging and drilling and mining as we have always done. And in the middle are the great majority of Americans who are not passionate either way, but want to be responsible consumers, and also to be able to visit grandma without breaking the bank.

I believe that the transition toward an energy system that is cleaner and less reliant on fossil fuels is realand will ultimately bring substantial benefits. At the same time, I believe that energy security and economics also matter. At a time when inflation was already running high, paying an average of $4.25 a gallon at the pump is piling pain on tens of millions of US households. Ultimately, over decades, the use of electric vehicles will reduce the need for oil and that lower-emissions sources, including renewables, will provide a larger share of the power supply, which today depends largely on gas and coal. But that moment is not now, or next week. Indeed, fossil fuels continue to account for almost 80 percent of US primary energy consumption, and a similar figure globally.

Here is one way to think about the interplay between the energy transition and energy security: “We need an energy strategy for the future—an all-of-the-above strategy for the 21st century that develops every source of American-made energy.” No, that isn’t some apologist for Big Oil; it was President Obama. In 2014, the Obama White House also noted the role of US domestic oil and gas production in enhancing economic resilience and reducing vulnerability to oil shocks. In short, the White House argued, US oil and gas production can bring real benefits for the country. I think that is still true.

Does that mean throwing in the towel on the energy transition and climate change? Absolutely not. There are a variety of ways to pursue the goal of reducing emissions and eventually getting to net-zero emissions. I’ve touched on many of them in previous posts—including reducing methane emissions,pricing carbon, hydrogen, renewables, electric vehicles, urban planning, carbon capture, and negative emissions technologies. In other words, an “all of the above strategy” makes sense in this regard, too.

I don’t know how, or if, a middle ground can be captured. But from what I heard at CERAWeek last year, from people of otherwise widely divergent views, there just may be momentum to get there. A middle-ground consensus rests on three premises. First, we need fossil fuels for energy security and reliability now and until the time when technologies are in place to secure the energy transition. Second, at the same time, we need to be investing in the energy transition because climate change is real and matters. And third, for sustained and systematic progress, government and industry need to work together.

Or, in a phrase, “all of the above.”

------

Scott Nyquist is a senior advisor at McKinsey & Company and vice chairman, Houston Energy Transition Initiative of the Greater Houston Partnership. The views expressed herein are Nyquist's own and not those of McKinsey & Company or of the Greater Houston Partnership. This article originally ran on LinkedIn.

Acquisitions and agreements fuel the top Houston energy news to knowCatch up on our top news for the first half of February. Courtesy photo

Acquisitions and agreements fuel the top Houston energy news to knowCatch up on our top news for the first half of February. Courtesy photo