How carbon capture works and the debate about whether it's a future climate solution

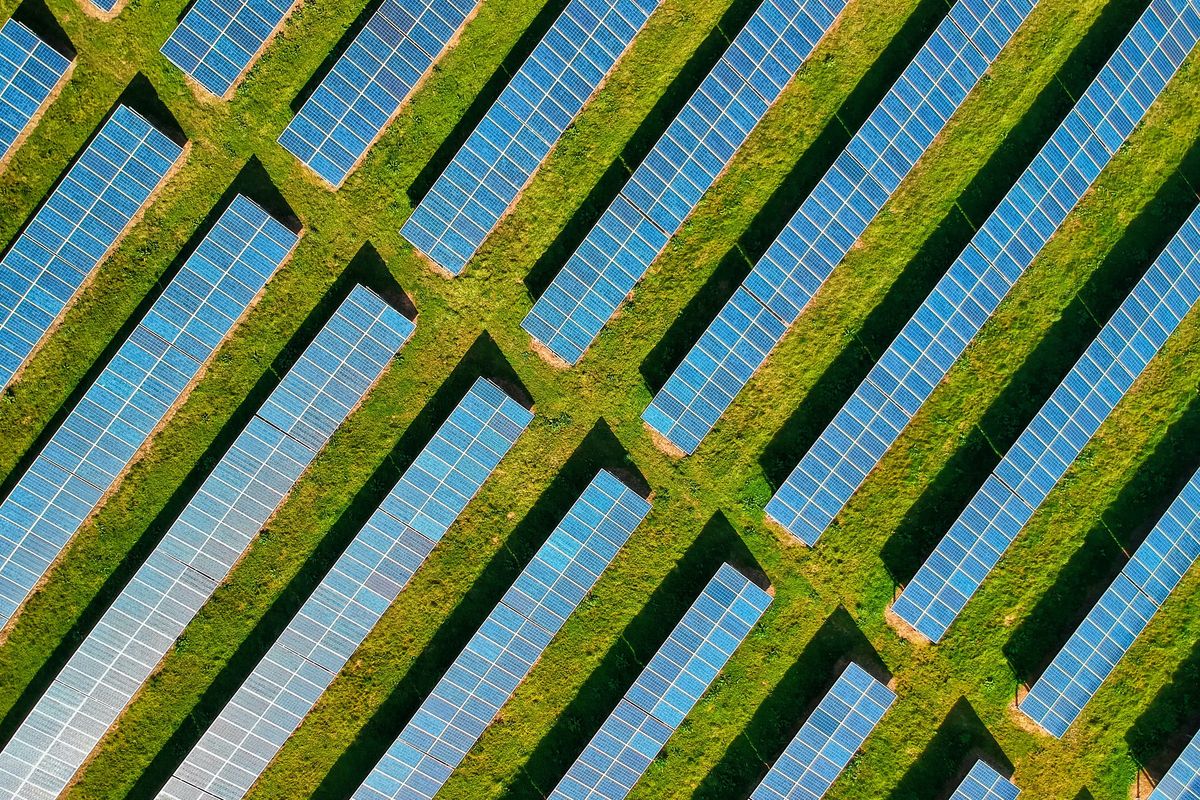

Energy Transition

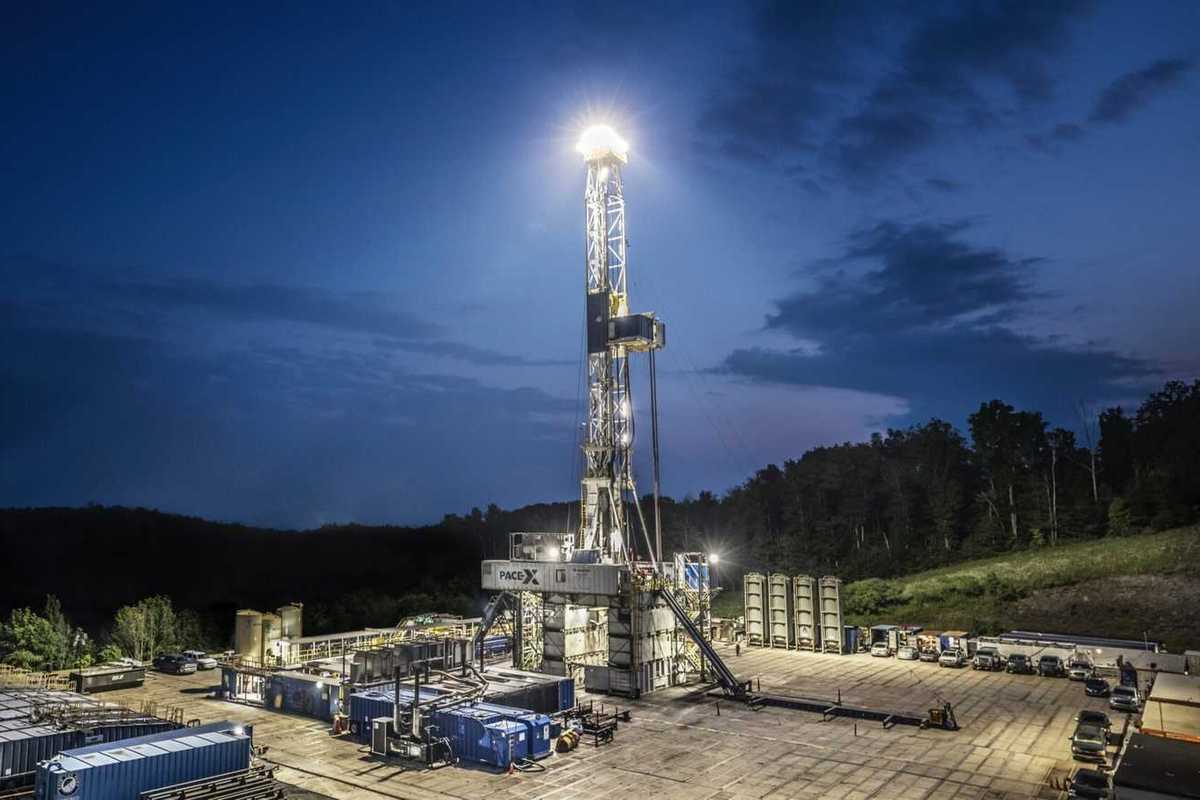

Power plants and industrial facilities that emit carbon dioxide, the primary driver of global warming, are hopeful that Congress will keep tax credits for capturing the gas and storing it deep underground.

The process, called carbon capture and sequestration, is seen by many as an important way to reduce pollution during a transition to renewable energy.

But it faces criticism from some conservatives, who say it is expensive and unnecessary, and from environmentalists, who say it has consistently failed to capture as much pollution as promised and is simply a way for producers of fossil fuels like oil, gas and coal to continue their use.

Here's a closer look.

How does the process work?

Carbon dioxide is a gas produced by burning of fossil fuels. It traps heat close to the ground when released to the atmosphere, where it persists for hundreds of years and raises global temperatures.

Industries and power plants can install equipment to separate carbon dioxide from other gases before it leaves the smokestack. The carbon then is compressed and shipped — usually through a pipeline — to a location where it’s injected deep underground for long-term storage.

Carbon also can be captured directly from the atmosphere using giant vacuums. Once captured, it is dissolved by chemicals or trapped by solid material.

Lauren Read, a senior vice president at BKV Corp., which built a carbon capture facility in Texas, said the company injects carbon at high pressure, forcing it almost two miles below the surface and into geological formations that can hold it for thousands of years.

The carbon can be stored in deep saline or basalt formations and unmineable coal seams. But about three-fourths of captured carbon dioxide is pumped back into oil fields to build up pressure that helps extract harder-to-reach reserves — meaning it's not stored permanently, according to the International Energy Agency and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

How much carbon dioxide is captured?

The most commonly used technology allows facilities to capture and store around 60% of their carbon dioxide emissions during the production process. Anything above that rate is much more difficult and expensive, according to the IEA.

Some companies have forecast carbon capture rates of 90% or more, “in practice, that has never happened,” said Alexandra Shaykevich, research manager at the Environmental Integrity Project’s Oil & Gas Watch.

That's because it's difficult to capture carbon dioxide from every point where it's emitted, said Grant Hauber, a strategic adviser on energy and financial markets at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

Environmentalists also cite potential problems keeping it in the ground. For example, last year, agribusiness company Archer-Daniels-Midland discovered a leak about a mile underground at its Illinois carbon capture and storage site, prompting the state legislature this year to ban carbon sequestration above or below the Mahomet Aquifer, an important source of drinking water for about a million people.

Carbon capture can be used to help reduce emissions from hard-to-abate industries like cement and steel, but many environmentalists contend it's less helpful when it extends the use of coal, oil and gas.

A 2021 study also found the carbon capture process emits significant amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas that’s shorter-lived than carbon dioxide but traps over 80 times more heat. That happens through leaks when the gas is brought to the surface and transported to plants.

About 45 carbon-capture facilities operated on a commercial scale last year, capturing a combined 50 million metric tons of carbon dioxide — a tiny fraction of the 37.8 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions from the energy sector alone, according to the IEA.

It's an even smaller share of all greenhouse gas emissions, which amounted to 53 gigatonnes for 2023, according to the latest report from the European Commission’s Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis says one of the world's largest carbon capture utilization and storage projects, ExxonMobil’s Shute Creek facility in Wyoming, captures only about half its carbon dioxide, and most of that is sold to oil and gas companies to pump back into oil fields.

Future of US tax credits is unclear

Even so, carbon capture is an important tool to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, particularly in heavy industries, said Sangeet Nepal, a technology specialist at the Carbon Capture Coalition.

“It’s not a substitution for renewables ... it’s just a complementary technology,” Nepal said. “It’s one piece of a puzzle in this broad fight against the climate change.”

Experts say many projects, including proposed ammonia and hydrogen plants on the U.S. Gulf Coast, likely won't be built without the tax credits, which Carbon Capture Coalition Executive Director Jessie Stolark says already have driven significant investment and are crucial U.S. global competitiveness.

Acquisitions and agreements fuel the top Houston energy news to knowCatch up on our top news for the first half of February. Courtesy photo

Acquisitions and agreements fuel the top Houston energy news to knowCatch up on our top news for the first half of February. Courtesy photo